John Howard had decided to join the United States-led invasion of Iraq before he took the matter to cabinet.

So adamant was he that no submissions to cabinet were ever made.

Instead, the then-prime minister relied on the dozens of discussions he’d had with the powerful National Security Council.

But what happened behind those closed doors, and whether the group ever considered the protracted conflict that would come from their invasion, remains secret.

Twenty years on from the war the United Nations branded “illegal”, to which Australia committed 2000 troops, a tranche of cabinet documents from 2003 have been released by the National Archives of Australia on Monday.

While hundreds of submissions and cabinet minutes have been released, documents from inside the powerful cabinet subcommittee are not captured in the Archives Act and remain unpublished.

Within the dossier that has been released, there is just one cabinet minute pertaining to the looming Iraq conflict from March 18, 2003 – the day before the invasion began – in which cabinet noted two oral submissions from Mr Howard.

In his address to cabinet, he stressed the belief Australia shared with the US and other like minded partners that Iraq possessed weapons of mass destruction and posed a risk to international security.

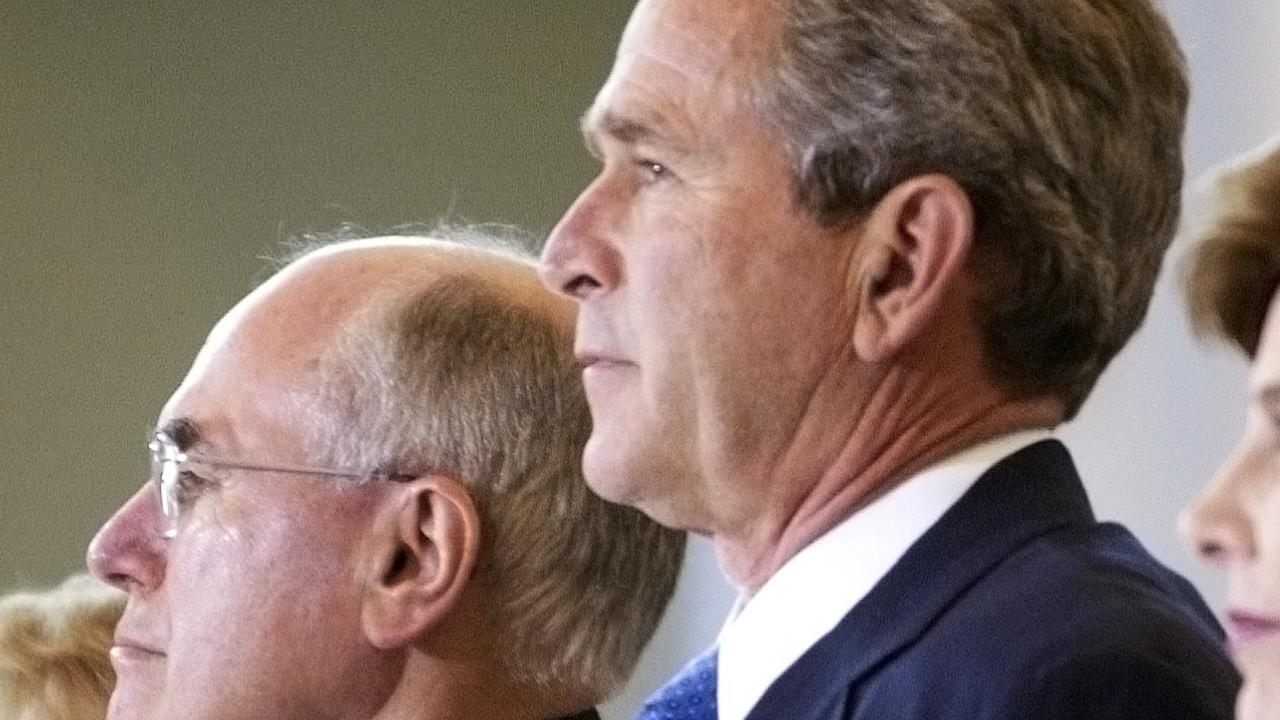

The oral reports he gave to cabinet on March 18, 2003 – the day before the invasion began – noted the “extensive” discussions Mr Howard had with then-US president George W Bush and then-UK prime minister Tony Blair.

The newly released documents reveal Mr Howard told cabinet that hours earlier, Mr Bush had requested Australia join the coalition of the willing to disarm Iraq if Saddam Hussein failed to comply with a freshly-issued ultimatum to surrender and leave Iraq.

The cabinet noted that all signs pointed to Iraq possessing the weapons, and what risk that posed to “international peace and security”; the “potential to damage gravely” Australia’s security; and the risk of those weapons falling into the hands of terrorists.

The cabinet noted Hussein had failed to comply with the United Nations Security Council’s resolutions, but although the council did not sanction the invasion, the US forged ahead.

Iraq a ‘political decision’

For cabinet historian David Lee, the cabinet documents – or lack thereof in the case of Iraq – reinforces that Mr Howard’s decision on Iraq was, as Robert Garran had written in 2004, “political, not based on a dispassionate appraisal of the threats it possessed”.

Mr Howard himself has since written that the decision to go into Iraq was not just because of Australia’s own belief that Iraq had weapons of mass destruction, but also because of the close relationship and alliance Australia had with the US.

“What we do see from this is that Howard, as a conservative PM in the sense of the government, wanted the decision on intervention to go to full cabinet. It does do that, just not with a submission,” Professor Lee said.

“The absence of a submission indicates to me that there was a strong disposition that the government is going to support this decision, and really, they don’t want any stumbling blocks in the way of going ahead with this decision.”

Professor Lee posits that a written cabinet submission from the department of foreign affairs and trade, or legal advice from the solicitor-general could have slowed down or hindered what Mr Howard saw as inevitable.

Professor Lee says the lack of submissions to cabinet reinforced how willing Mr Howard’s government was to join the US.

“If the cabinet wanted a submission, it would (ask),” he said.

“It is regrettable that this didn’t happen because had cabinet had a full picture of the nature of the intelligence, the nature of Iraq, the potential geopolitical changes such as making Iran more powerful – these are all things that argued against the decision.”

Robert Hill, who was defence minister from 2002, said there are “a few lessons” to learn,

He said debate on whether or not Australia should take up the US’ request had happened, just not in front of the whole cabinet.

“Certainly the costs and the capabilities that we might best contribute and what were the risks associated with (the decision) … all of that in depth analysis, all of those issues were debated within the NSC,” he said.

“The difficulty with the full cabinet is that it’s not really structured for that detailed debate and analysis.”

Cabinet may not have received submissions or been the site of any discussion, but then-defence minister Robert Hill says that was all happening in the National Security Committee.

The cabinet minute from March 18 noted a memorandum of advice provided from, among others, the attorney-general’s department, that said the use of force against Iraq would be “consistent with Australia’s obligations under international law”.

The attorney-general “fully concurred with the advice”.

Mr Hill said cabinet had felt confident in its legal justification.

“In the end, our justifications was the flow on from the two UN resolutions, when we believed we couldn’t be satisfied with the requirements put on him (Saddam),” he said.

Professor Lee said Mr Howard might have faced a tougher time joining the invasion had the Governor-General at the time not been a clergyman.

Peter Hollingworth had sought the views of the attorney-general on the matter, to which Mr Howard intervened, telling him “no involvement was necessary” because any decision could be made without recourse to him.

“Had the governor-general in 2003 not been a clergyman but a lawyer as versed in constitutional law and practice as Kerr or Sir Ninian Stephen or Sir William Deane all were, he or she may well have insisted on advice from the attorney-general,” he posited.

The aftermath

In the end, the coalition never found the weapons, and the invasion soon descended into a regime topple that ultimately led to insurgency and to a civil war, with the protracted conflict continuing until 2011.

The newly released documents suggest cabinet in 2003 did not consider what might happen in the aftermath of the invasion.

Mr Hill said that 20 years of reflection had proved powerful, conceding there were things the government could have done better.

“Maybe we should have been more sceptical and kept pressing the intelligence services, but the difficulty was that all of the major intelligence services around the Western world held the same view (that Iraq had WMDs),” Mr Hill said.

“So maybe we (could have done things better), but I don’t know that even if we had persevered longer on that issue it would have added more clarity.

“There have been a few lessons, and I do think it is important to try to learn from history and try to learn from these experiences what goes right and what goes wrong.”

In the weeks after the invasion began, Mr Howard updated cabinet sporadically.

On April 1, cabinet noted an oral report from Mr Howard regarding the “progress of military operations and the contributions made by the ADF”.

Then, in June, the NSC noted the conflict in Iraq was having an impact on Australia’s humanitarian program.

In a submission from the immigration minister, Phillip Ruddock noted that – in keeping with the Howard government’s broader strategy on tackling people smuggling and irregular migration – the government would need to work to ensure both voluntary and involuntary returns of Iraqis were done “in a timely manner”.

He added that Iraqis had made up 41 per cent of all illegal boat arrivals between 1999 and 2001.

Professor Lee said it remained a mystery whether the political fallout of the invasion had any bearing on Mr Howard’s decision, saying he hoped those documents might soon be released.