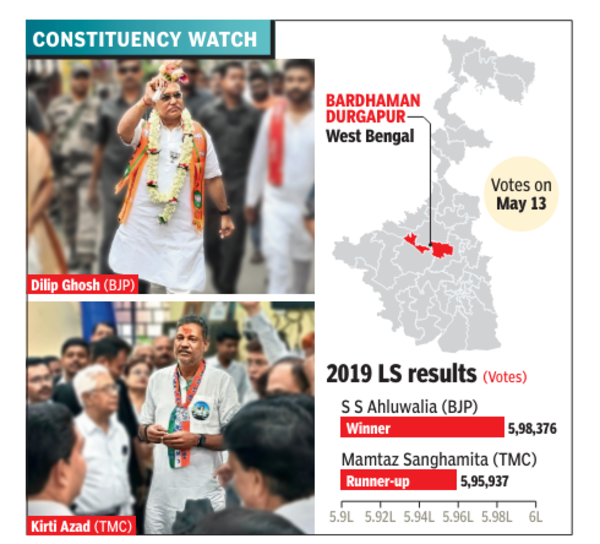

On March 10, Trinamool shook up the poll scene when it fielded cricketer Kirti Azad, a member of the 1983 World Cup winning team, as its candidate here.Three weeks later, BJP came up with an even bigger surprise by naming its outspoken but controversial battle-hardened campaigner, Dilip Ghosh, for the constituency.

Ghosh (59), who had won the 2019 Lok Sabha elections from Midnapore, has taken the change of seat in his stride. “The party sent me to Andaman, and I helped build a base there. I was sent to Kharagpur and won. I was asked to contest from Midnapore and emerged victorious. Aami Trinamool ke jawab di aar party ke ashon di (I respond to Trinamool and deliver seats to my party,” he says.

Ghosh adds, “I don’t think I was ousted from Midnapore. I am a full-time party worker who doesn’t have a choice. So, when I was told to contest from the Burdwan-Durgapur Lok Sabha constituency, I came here the very next day.” “Maybe this is a weak seat and the party needed me here,” he says.

A former state BJP president, Ghosh has an enviable political record. Groomed in RSS, he won the assembly polls from Kharagpur in 2016. With him at BJP’s helm in Bengal, the party got a whopping 40.7% vote share in the 2019 general elections in the state. “Ami jongol saaf korechi, aaj okhane building hochche (I have cleared the forests, now buildings are coming up there),” Ghosh says.

Like Ghosh, Azad never sticks to the staid political script. “Didi is mahishasuramardini and Ghosh is kaliyug’s mahishasura,” Azad says, expressing confidence that he will win by over a lakh votes.

Unlike Ghosh, Azad has the cushion of a stronger party base. In the 2021 assembly polls, Trinamool won six of the seven assembly segments that make up for this Lok Sabha seat. Extrapolating it, the total difference of votes between the BJP and Trinamool across the seven assembly segments was 97,000.

In the 2019 LS polls, BJP had won this seat by 2,439 votes.

The Bardhaman-Durgapur Lok Sabha constituency has never returned a party to the Lok Sabha twice in succession. While CP(M) won from the seat in 2009, Trinamool and BJP emerged victorious in 2014 and 2019, respectively. The constituency has a Muslim population of nearly 20%, while the Scheduled Castes account for 27%. It is a high-stakes fight, which neither Dilip nor Kirti deny.

Ghosh’s biggest challenge, however, is to overcome its weak organisation in this constituency. Besides, he needs to consolidate the anti-Trinamool votes. CP(M) has fielded Sukriti Ghosal, a former principal of Burdwan Women’s College. “I will tell people not to vote for CP(M), as it will help Trinamool ultimately,” he says.

The Left and Congress, contesting separately, had cornered 13.8% votes in the 2019 Lok Sabha elections, which they contested together. But fault lines have appeared in 2024. Ghoshal, who has roots there, has faced resistance from several Congress workers. Many local Congress leaders are alleging that CP(M) announced its candidate without holding consultations.

On the face of it, Azad has the comfort of a stronger organisation. But it is also riddled with factionalism in the ranks. On March 31, while campaigning in the Durgapur area, Azad got caught in the middle of a scuffle between the supporters of two factions of the party. But Azad dismisses this as a “one-off incident in a bigger party.”

Beyond the high-decibel campaign, in which both Ghosh and Azad are matching each other word for word, BJP’s strategy is primarily to recover lost ground it ceded to Trinamool in the industrial zones of Durgapur East and West assembly segments. Trinamool is desperately trying to hold on to its leads in the five rural belts. “I expect a massive lead from Durgapur, more than Burdwan,” Ghosh candidly said.

Azad’s campaign, meanwhile, is focused on the unavailability of central funds, CAA and communal rifts. “Lakshmir Bhandar will be a game-changer,” he asserts.