Because, late within the bowels of the Stade de France, long after the crowds had departed and the gold dust settled in an empty stadium, the Indian, just dethroned, was telling us how it was great that India still had a medal despite his five fouled attempts in the final.It was perhaps a first of sorts for the Indian, usually more accustomed to speaking from the top of the pile.

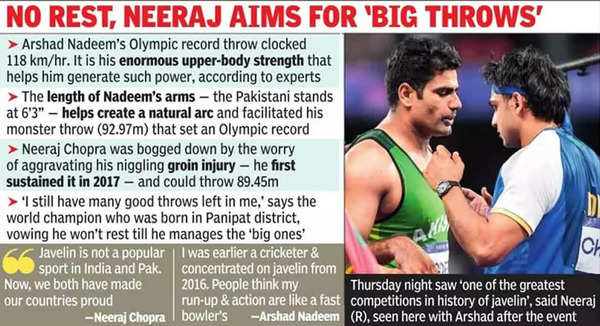

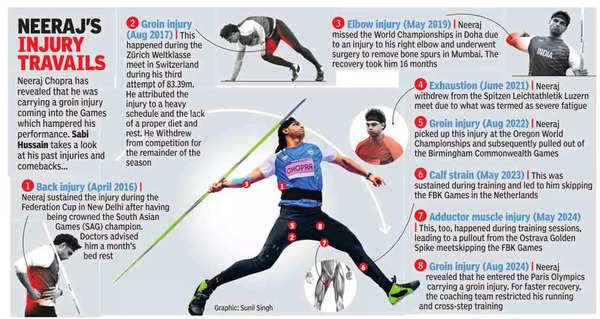

What Neeraj said was that there probably now existed a need for a new challenge, after having won everything that was on offer – his World Championship gold in Budapest last year completing a glittering circle. “I have won all the biggest prizes in the world of javelin. I have been in the 88-89m range for years now. I have full faith in my arm,” he said.

“The big throw will come,” he added enigmatically. What he didn’t say explicitly was that the 90m barrier in competition becomes the albatross now. After his Budapest gold last year, when asked if it affected him that his top podium finishes came without breaching the 90m mark, Neeraj had said: “When the 90m will come, it will come. I am not really allowing that to trouble myself with that right now.”

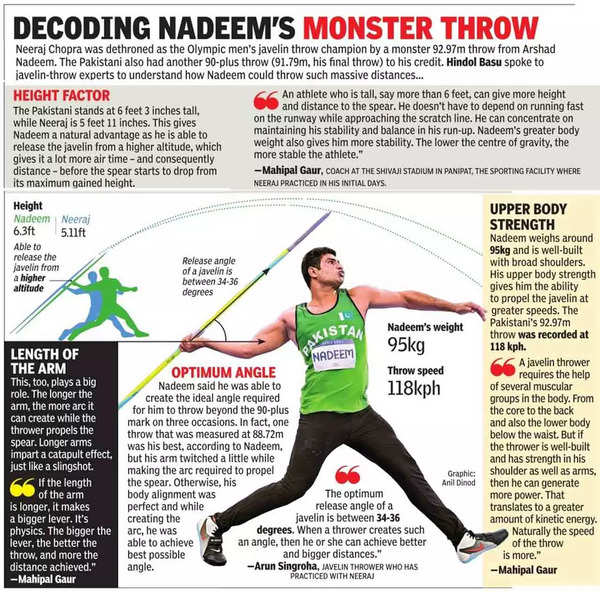

The entire thinking was forced to take on a different meaning in Stade de France on Thursday, when Nadeem was throwing massive 90-plus in the final like some bored bar regular flicking match boxes into an empty glass – so casual and in control he looked.

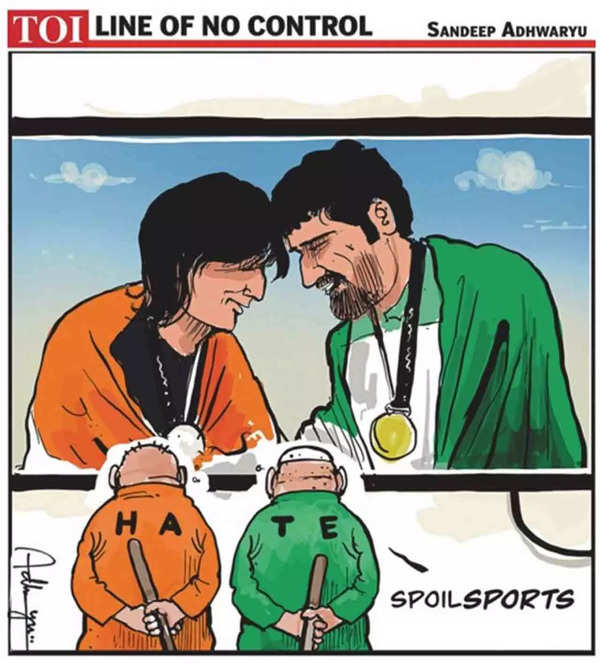

Clearly, there’s an elite South Asian axis forming in javelin, a much-needed elite rivalry in Indo-Pak sports in a time when bilateral cricket is taboo and hockey as good as over. This was evident in the slightly forlorn figure that bronze winner Anderson Peters presented at the press conference later, totally ignored as Nadeem and Neeraj fielded almost all of the questions.

For the first time in Olympic history – 27 Games and 116 years apparently – three men of colour took the javelin podium.

With Nadeem solidifying his credentials in Paris in such emphatic fashion, it becomes necessary to understand what he is all about. A run-up in javelin as minimal as Shane Warne’s in Test cricket, but as deceptive and devastating in impact. The 27-year-old father of three with dodgy knees is probably an aberration in the most scientific of events in athletics.

On Thursday, there seemed a distinct manner in his spear’s flight – climbing in the air and then deciding when to park itself. The highly shortened run-up and the result gave an idea of the power of the arm of the man from Pakistan.

But ask him to explain his craft, and the secrets behind it, the man is at a loss, often lapsing into expressing gratitude to the almighty and his coach, Salman Iqbal Butt.

Somewhere, having to shelve ambitions of becoming a fast bowler for Pakistan, Nadeem owes his run-up to his early days as a school and college student.

The son of a brick mason from Mian Channu village in Pakistan’s Punjab province, Nadeem has been beset by injuries ever since he picked up the javelin. Indeed, injured as recently till January, he owes his resurgence to London-based Dr Ali Sher Bajwa whose treatment provided such fantastic results in Paris on Thursday.

But it didn’t begin this way. Nadeem’s first throw was short of abysmal, probably reaffirming the usual trope about him by his baiters in India as just another faulty product from across the border.

Ask him about this, and he laughed, “Arrey no, I was in such a fantastic frame of mind, such good shape that I even forgot my run-up. Hota hai…” After what eventually transpired, even his worst critics would nod in awe and admiration and admit that yes, miracles do happen.

Neeraj Chopra, his brother from another mother, had been telling us all along. In Paris on Thursday, Nadeem proved Neeraj right.