The November 10 judgment, passed on a plea by the Mann government in Punjab against governor Banwarilal Purohit, was uploaded on Thursday on the SC website.The bench of CJI D Y Chandrachud and JusticesJ B Pardiwala and Manoj Misra said unbridled powers to “unelected head of state” to sit indefinitely over bills “virtually veto the functioning of the legislative domain by a duly elected legislature by simply declaring that assent is withheld without any further recourse”.

“Such a course of action would be contrary to fundamental principles of a constitutional democracy based on a parliamentary pattern of governance,” said Justice Chandrachud, who authored the judgment.

The bench also held that the speaker enjoys absolute power for adjourning and proroguing the House. “It is the right of each House of the legislature to be the sole judge of the lawfulness of its own proceedings so as to be immune from challenge before a court of law. During the tenure of the assembly, the House is governed by the decisions which are taken by the speaker in matters of adjournment and prorogation,” the order said.

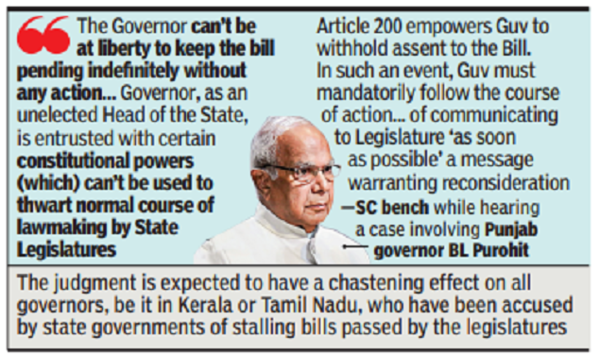

The judgment is expected to have a chastening effect on all governors, be it in Kerala or Tamil Nadu, who have been accused by state governments of stalling bills passed by the legislature, although the apex court stopped short of setting a timeframe for Raj Bhavans to take an early decision — essentially on withholding assent and sending the legislation back to the assembly for reconsideration.

“The governor cannot be at liberty to keep the bill pending indefinitely without any action whatsoever. The governor, as an unelected head of the state, is entrusted with certain constitutional powers. However, this power cannot be used to thwart the normal course of lawmaking by the state legislatures,” the CJI wrote.

“Consequently, if the governor decides to withhold assent under the substantive part of Article 200, the logical course of action is to pursue the course indicated in the first proviso of remitting the bill to the state legislature for reconsideration,” the court said.

CJI Chandrachud termed democracy and federalism as “two prongs of a tuning fork” which work towards realisation of fundamental freedoms and aspirations of citizens and said, “Whenever one prong of the tuning fork is harmed, it damages the apparatus of constitutional governance.”

Dealing with the issue central to the debate — the Constitution’s silence over the period within which a governor is to take a decision on whether to give assent, the mandatory pre-requisite for enactment of a bill — the bench suggested that it could not be interminably long.

“The substantive part of Article 200 empowers the governor to withhold assent to a bill. In such an event, the governor must mandatorily follow the course of action which is indicated in the first proviso of communicating to the state legislature ‘as soon as possible’ a message warranting reconsideration of the bill,” the bench said.

State govt vs Governors: Supreme Court raises questions over delay in Bill approval

“The expression ‘as soon as possible’ is significant. It conveys a constitutional imperative of expedition. Failure to take a call and keeping a bill duly passed for indeterminate periods is a course of action inconsistent with that expression. Constitutional language is not surplusage,” the bench added.