Chinese authorities declined to comment on the motive behind the attack on a 10-year-old boy stabbed this week near his Japanese school in Shenzhen. Police in the southern tech hub didn’t mention the victim’s nationality in an initial statement.

Chinese Foreign Ministry spokesman Lin Jian said he was “saddened” by the killing, calling it an “individual case” during a regular press briefing on Thursday in Beijing.“China will continue to take effective measures to protect all foreign nationals,” he added.

Months earlier, authorities also described a knife attack on a Japanese woman and child, and the stabbing of four teachers from a US college, as “isolated” incidents. The date of this week’s tragedy stood out: It fell on the anniversary of an event that triggered Japan’s invasion of China — now National Defense Education Day, when sirens sound in many cities across the country.

The ruling Communist Party has legitimized its policies by promoting a strong China on the world stage in recent years, a tactic that’s brewed growing hostility toward the US and its allies including Japan. With unrest mounting over China’s economic slowdown, the government is now grappling with online hatred spilling over into real life violence.

“Chinese authorities have certainly normalized nationalism as the ‘correct’ way to understand the world,” said Florian Schneider, chair professor of modern China at Leiden University. “What citizens then do with that understanding is not up to any individual leader — and it can backfire, sometimes spectacularly so.”

On social media, Chinese users were critical. “Who tolerated hatred comments online?” one person asked under the Japanese Embassy in China’s post about the attack on the X-like Weibo. “The hatred education has had remarkable results,” read another top-voted comment.

But while nationalism might have provided a catalyst for the recent outbursts of violence, Schneider cautioned that “the roots are likely much deeper, tying in with broader social and economic anxieties.”

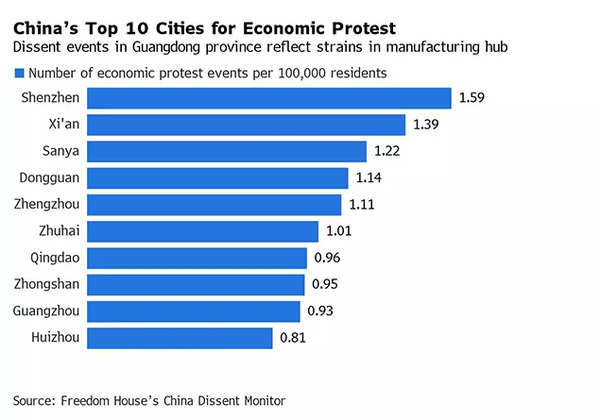

China’s property slump has wiped some $18 trillion in wealth from households, according to Barclays Plc calculations, and triggered pay cuts and layoffs as the nation wrestles with its longest period of deflation in decades. Earlier this year, Chinese social media users connected those economic pressures to an uptick in violent attacks.

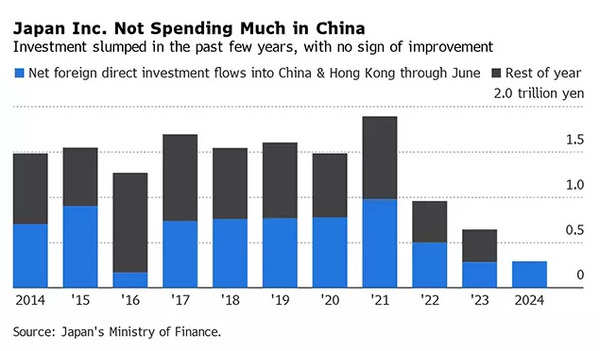

Public acts of violence against foreigners undercut Beijing’s broader goal of attracting overseas business at a time of sagging investment. Almost half of Japanese firms in China polled recently said they won’t spend more or will cut investment this year — citing rising wages, falling prices and geopolitical tensions.

“The current knifing incident may be an additional concern to add on to such issues,” said Lim Tai Wei, adjunct senior research fellow at National University of Singapore’s East Asian Institute, noting the latest incident comes at a time of some thawing in bilateral relations.

Generations of Chinese citizens have grown up exposed to hostile propaganda toward Japan. Beijing claims Tokyo hasn’t apologized sufficiently for war atrocities and is embroiled in territorial spats over disputed islands in the East China Sea. Those tensions have deepened as Asia’s largest economies compete in a wide array of commercial fields, and Tokyo forges closer military and trade ties with the US.

Beijing fanned anti-Japan sentiment last year by rebuking Tokyo’s plan to release treated water from the Fukushima nuclear plant, and banning all seafood from its neighbor. That decision defied scientists’ assessments the move was in line with global safety standards.

Highlighting the growing antagonism, a Chinese influencer recently posted a video of himself desecrating the war-linked Yasukuni Shrine, associated with Japan’s history of military aggression. That act drew from some Chinese social media users criticizing the show of extreme nationalism.

A viral Wechat article titled “I Still Feed Sad For That Japanese Boy” similarly questioned the growing anti-Japan rhetoric that has become mainstream over the past decade.

“The voices supporting friendly exchanges between China and Japan have gradually been marginalized, or even cleansed online,” wrote the author in a post that has been over 12,000 times and had over 4,000 likes by Thursday afternoon.

Such narratives “will eventually spill offline and have influence over the real world,” the author wrote. The article was later censored “due to violations.”

It’s a risk the nation’s leaders seem to understand.

Beijing has reined in its “Wolf Warrior” diplomats, and is trying to stabilize ties with the US through a flurry of high-level diplomatic talks. After the June stabbing of a Japanese woman and child, Chinese authorities gave the bus attendant who sacrificed her life to save them a hero’s award, commending her efforts to help the foreigners.

The extent of the challenge to shift sentiment was exemplified this week when the World Table Tennis association was attacked by Chinese fans for choosing to sell tickets for an event in Fukuoka — a city in Japan — on the same date of Tokyo’s invasion of China. Eventually, organizers relented.

“The Communist Party has built nationalism as a form of legitimacy, but it’s like riding the target,” said Geoff Raby, former Australian ambassador to China. “It can’t always control it in its own interest.”