Justice Chandrachud became CJI on November 9 last year and has one more year to go in the top post.

On completion of one year in office, CJI D Y Chandrachud tells Dhananjay Mahapatra that Supreme Court judges are well insulated and unconcerned with the vicissitudes of everyday public perception while deciding cases. Excerpts:

What has been the experience as Chief Justice of one of the largest democracies in the world?

The scale and diversity of India makes it truly unique. The Supreme Court, despite sitting in New Delhi, deals with legal issues arising from every corner of the country. An interesting by-product of our Constitution is that although we have a federal system of governance, our judiciary is unitary. Thus, appeals from across the entire country work their way up to the Supreme Court.

Further, the court is both an appellate court and a constitutional court. As Chief Justice, I am acutely conscious that this requires a balance, between deciding the cases of ordinary citizens on the one hand, and answering important constitutional questions that concern the nation as a whole, on the other. To meet these demands, we are increasing the rate at which the court hears cases, while also continually hearing crucial constitutional cases.

As Chief Justice, not only do I have to decide claims from diverse groups of citizens, I also have to pay attention to the important task of justice delivery across the nation. This means ensuring not just the Supreme Court and high courts are able to operate with integrity and efficiency, but also the district courts across the country are accessible and useful to citizens of all strata of society.

While this can seem like a lot, I think all judges should take immense pride in their work. As you mentioned, India is the largest democracy in the world and the judiciary has played an important role as a governance institution in ensuring that the institutions of the country are working for the people.

Is the work, both administrative and judicial, as an SC judge very different to that of the CJI?

All judges of the Supreme Court do some administrative work assigned by the Chief Justice. We have committees of judges responsible for various aspects of court administration such as staff welfare and promotions, the Supreme Court Library, case management, and the construction of new infrastructure.

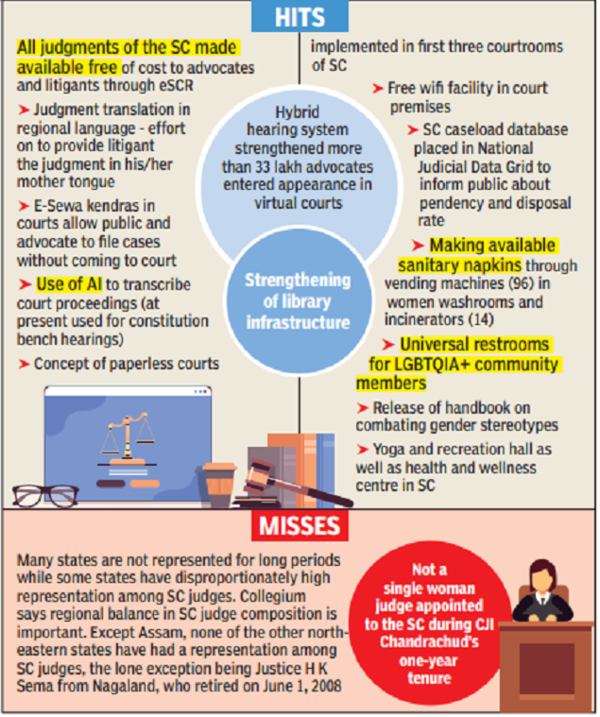

However, the role of the Chief Justice is distinct for two reasons. First, the final decision-making authority on all administrative issues rests with the Chief Justice’s office. In this context, much of my administrative work is conceiving and coordinating the rollout of new initiatives such as e-SCR which has made available 34,000 judgments available online free of cost, the construction of universal restrooms in the Supreme Court to meet the needs of the LGBTQIA+ community, or ensuring the continued development of ICT-enabled courtrooms across the country.

The Chief Justice’s administrative responsibilities extend far beyond the Supreme Court. For example, the Chief Justice is the patron-in-chief of the National Legal Services Authority, the Visitor of several law universities, the president of the Indian Law Institute, etc. This aspect sets the CJI’s role apart as he must provide a vision, not just for the Supreme Court but for the judiciary as a whole. For instance, through the Chief Justices’ and Chief Ministers’ Conference, the Chief Justice makes efforts to emphasise a national agenda related to the judiciary. Thus, the Chief Justice’s role is not just deciding cases and ensuring the working of the court, but also looking to the future.

Does public perception matter to judges in deciding matters involving conflict of rights? Does the SC lean towards protecting fundamental rights even in situations conflicting with national interest?

Judges at all levels of the Indian judiciary have received training on how to remain impartial even in controversial or sensitive cases. On the one hand, we must remember that judges are human, they read the newspaper, they watch television, and they talk to people.

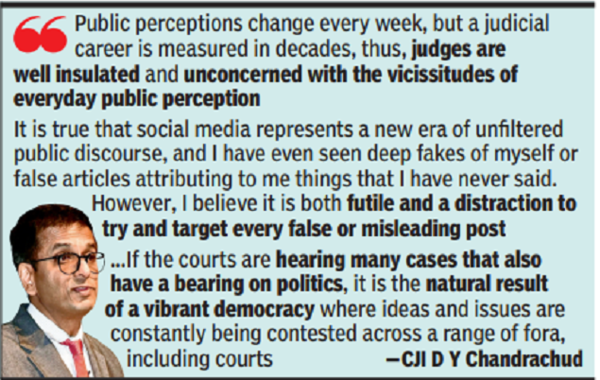

However, the training judges receive, the quiet lives they lead, the important safeguards that protect judicial independence and the moderating influence of the bench as a whole, allows judges to decide cases impartially irrespective of public perception. You must remember that public perceptions change every week, but a judicial career is measured in decades, thus, judges are well insulated and unconcerned with the vicissitudes of everyday public perception.

It’s true that social media represents a new era of unfiltered public discourse, and I have even seen deepfakes of myself or false articles attributing to me things I have never said. However, I believe it is both futile and a distraction to try and target every false or misleading post on the internet. Certainly, when a post gains a lot of traction and may undermine judicial proceedings, it must be responded to

CJI D Y Chandrachud

With respect to fundamental rights, of course, judges, particularly at the Supreme Court, are often called to balance national interest with individual rights-claims. The Constitution guarantees citizens rights that the courts are duty-bound to protect. However, these rights are subject to reasonable restrictions.

The role of the court is to ensure that the actions of the government, even when pursuing the national interest, always respect the rule of law and the Constitution. It is really for commentators and academics to decide which way the court ‘leans’, and they are entitled to their opinions. But the task of the judge is to decide each case on its merits within the framework provided by the Constitution.

Does contempt of court law require a revisit in the era of social media where people express whatever comes to their mind irrespective of the harm it causes to reputation, dignity and public life of individuals and institutions?

The power to punish for contempt of court exists to prevent individuals from interfering with the operation of the court, not to protect the reputation of judges. For example, if someone is in wilful disregard of a court order or creates commotion in court and prevents proceedings from taking place, such a person may be in contempt.

But I strongly believe that the court’s contempt powers should not be used to protect judges from criticism. The reputation of judges and the courts must stand on a stronger footing than the fear of being punished for contempt. It must be based on the work and decisions of judges.

It is true that social media represents a new era of unfiltered public discourse, and I have even seen deep fakes of myself or false articles attributing to me things that I have never said. However, I believe it is both futile and a distraction to try and target every false or misleading post on the internet.

Certainly, when a post gains a lot of traction and may undermine judicial proceedings, it must be responded to. But in the long run, I believe that it is important for the court to have authoritative communication channels with the media and citizens.

For example, we are in the process of launching a newsletter to communicate the work being done by the court directly to the people. Where citizens have access to authoritative sources of information through institutions and the media, the reliance on such unverified content will eventually decrease.

Do 160-year-old penal laws need a relook to make them more humane and time sensitive?

This is a question for Parliament to consider. Certainly, we have struck down certain provisions of the Indian Penal Code because they were not constitutionally compliant, most notably Section 377 which criminalised consensual sexual intercourse among individuals of the same sex. However, it is not the court’s role to consider the desirability of larger legislative changes absent specific challenges before us.

How far have we as a nation succeeded in achieving gender justice? What role do you foresee for the SC in this regard?

The quest for gender justice is ever evolving. The milestone is how much still needs to be done towards achieving gender equality. When the late Justice Ginsburg of the nine-member US Supreme Court was asked how many women ought to be in the US Supreme Court, she said nine, ie, all of them. After all, we have had all-male Supreme Courts for a long time, why should an all-woman Supreme Court surprise us?

But in addition to ensuring diversity on the bench, we also have several cases on gender justice that the court regularly hears. In this regard, you can look at a multitude of decisions where the court has protected gender equality and upheld the constitutional mandate for the empowerment and upliftment of women.

We have decisions outlawing the infamous two-finger test for victims of rape or the grant of permanent commission to women officers in the armed forces. These are just some examples where the court has succeeded in advancing gender justice.

Even beyond the courtroom, the court can play an important role. For example, this year we released a ‘Handbook on Combating Gender Stereotypes’ which contained a glossary of gender-unjust terms. This can help both judges and citizens avoid the use of degrading language or language that hides incorrect assumptions about women.

PIL was a novelty created by the SC to give voice to the poor and marginalised. Do you think it is being abused for political, partisan and economic purposes? Do constitutional courts need to have a fresh look at the manner in which a PIL can be filed?

PILs have been an invaluable tool in ensuring access to justice. They have allowed citizens from all corners of the country to approach the Supreme Court even when they may not have the economic or social capital to otherwise raise the important issues they bring to the courts.

As for abuse, the Supreme Court has already framed guidelines concerning the circumstances in which PILs can be filed. Further, the court’s registry scrutinises petitions to make sure they raise concrete legal issues. Finally, as the popular saying goes, the law may be blind, but the judge sees all. Judges are adequately trained to weed out PILs that are frivolous or amount to an abuse of the legal process. Given these safeguards, I do not think that the court needs to restrict PILs, as this may lead to a denial of access to justice.

Politics and judiciary are two distinct spheres. Yet, one sees increasing use of judicial platforms for settling political scores. Your views.

First, I think there is an incorrect perception that the court is continually deciding high-profile political cases. The vast majority of work done by courts across the country, including the Supreme Court, concerns the legal dispute of individual citizens and has nothing to do with politics. These concern land disputes, pension claims or criminal cases.

However, because cases involving political figures or causes get substantially more media coverage than cases involving citizens, it creates a perception that the court is heavily involved in the political arena.

I think that legal issues have always had a close bearing on political disagreements. Of course, the executive and legislature operate in a different domain from the judiciary. But whether it is the constitutionality of laws, disputes concerning elections, or criminal proceedings involving public figures, courts always have had a role to play in ensuring that politics operates within the confines of the rule of law and the Constitution.

I think that if the courts are hearing many cases that also have a bearing on politics, it is the natural result of a vibrant democracy where ideas and issues are constantly being contested across a range of fora, including courts.

Trial courts are the backbone of the judiciary. At many places, judicial officers are not provided with basic infrastructure despite the SC getting actively involved.

One of the key ways in which the Supreme Court works towards improving judicial infrastructure is to play a coordinating role. For example, the National Court Management Systems Committee and the e-Committee of the Supreme Court lay down important standards to be adhered to in building new infrastructure.

It is not enough to build new infrastructure, but we have to be inclusive when we build. For example, including accessibility ramps for persons with disabilities or having female washrooms that dispense sanitary napkins ensure that court infrastructure is welcoming to everybody.

Likewise, we have to build for the future, ensuring that newly-constructed courts are ICT capable for the technological demands of the years to come. Phase III of the Supreme Court’s e-Committee project has apportioned over Rs 7,000 crore to be spent on important infrastructure ranging from case-digitisation efforts, e-filing and video-conferencing facilities, and high-speed internet connectivity and new ICT hardware for all courts.

In line with this coordinating role of the Supreme Court, we have set up the i-Juris portal where courts across the country are constantly uploading and updating data on the state of judicial infrastructure. The database is updated almost daily. Through this portal, I can tell you that just this year, construction has begun on more than 500 district courtrooms across the country.

Through i-Juris, the Supreme Court is able to maintain a birds eye view of the state of judicial infrastructure throughout the country which will undoubtedly help both the government and the judiciary identify weaknesses and correct them. The coordinating role of the Supreme Court highlights how building judicial infrastructure is a fundamentally collaborative process involving the Union and state governments, the high courts and the Supreme Court and I believe we are heading in the right direction.